Climate change is often discussed in terms of environmental degradation, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events. However, its profound effects extend beyond physical landscapes and infrastructure; the emerging link between climate change and mental health is gaining recognition among researchers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers. A recent comprehensive study reveals that climate-related stressors—including heat waves, natural disasters, and long-term environmental changes—can significantly exacerbate mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Understanding these connections is critical for developing holistic strategies that address both environmental and psychosocial well-being.

The Psychological Toll of Extreme Weather Events

Extreme weather events—such as hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and prolonged droughts—have immediate and long-lasting psychological consequences.

A. Acute Stress and Trauma Response

-

Survivors of hurricanes and floods often experience acute stress reactions, characterized by hypervigilance, intrusive memories, and sleep disturbances.

-

Emergency responders and cleanup crews can develop compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress.

B. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

-

Studies indicate that up to 30% of disaster survivors meet criteria for PTSD in the aftermath of a major event.

-

Repeated exposure to disasters, as seen in regions hit by successive wildfires, multiplies PTSD risk.

C. Grief and Loss

-

Loss of home, livelihood, or loved ones triggers profound grief.

-

Community-wide losses—such as entire neighborhoods destroyed by fire—can erode collective identity and social support networks.

D. Displacement and Uncertainty

-

Climate refugees face the psychological burden of leaving ancestral land, navigating unfamiliar environments, and coping with legal insecurity.

Chronic Environmental Stressors and Mental Health

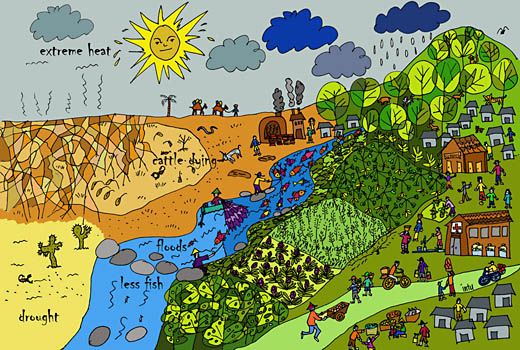

Beyond acute events, slow-onset changes such as rising temperatures, sea-level rise, and ecological degradation also take a toll on mental well-being.

A. Eco-Anxiety

-

Defined as chronic fear of environmental doom, eco‑anxiety manifests as persistent worry, sleep disturbances, and difficulty concentrating.

-

Young adults and adolescents, who inherit a more uncertain future, report higher levels of eco‑anxiety.

B. Solastalgia

-

Coined to describe distress caused by environmental change affecting one’s home environment.

-

Residents of mining regions, deforested areas, or receding coastal zones can experience mourning for landscapes undergoing irreversible transformation.

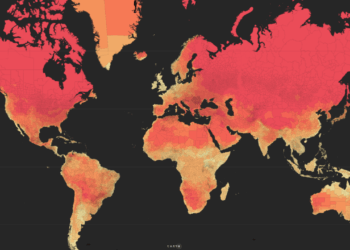

C. Heat-Related Mood Dysregulation

-

High ambient temperatures correlate with increased irritability, aggression, and risk of mood disorders.

-

Heat waves have been linked to spikes in emergency psychiatric admissions.

D. Food and Water Insecurity

-

Agricultural disruption from drought leads to anxieties about food availability, malnutrition, and economic hardship.

-

Scarcity can foster community tension, social unrest, and mental health crises.

Mechanisms Linking Climate Stress to Psychological Distress

The pathways through which climate change impacts mental health are multifaceted, encompassing biological, social, and environmental interactions.

A. Physiological Stress Response

-

Chronic activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis due to prolonged stress elevates cortisol levels, contributing to anxiety and depression.

B. Neuroinflammation

-

Extreme heat and pollutants can induce systemic inflammation, crossing the blood-brain barrier and affecting neurotransmitter systems.

C. Social Determinants

-

Vulnerable populations—low-income communities, indigenous groups, and the elderly—face disproportionate exposure and have fewer resources for recovery.

D. Community Disruption

-

Disasters shatter social cohesion; displacement undermines support networks essential for emotional resilience.

E. Chronic Uncertainty

-

Continual anticipation of future disasters fosters a state of “pre‑traumatic” stress, undermining hope and life satisfaction.

Populations Most at Risk

Certain groups bear the brunt of climate‑induced mental health burdens.

A. Children and Adolescents

-

Developing brains are particularly sensitive to stress; early exposure increases lifetime risk of psychiatric disorders.

-

School closures and habitat loss disrupt routine and social development.

B. Elderly Individuals

-

Physical vulnerabilities limit mobility during evacuations, intensifying feelings of helplessness.

-

Isolation compounds anxiety when support services falter post-disaster.

C. Low‑Income Communities

-

Financial constraints impede evacuation, home repairs, and access to mental healthcare.

-

Housing instability and neighborhood degradation perpetuate chronic stress.

D. Indigenous and Rural Populations

-

Cultural ties to land mean ecological damage threatens identity and traditional practices.

-

Remote locations often lack mental health infrastructure.

E. First Responders and Relief Workers

-

High exposure to traumatic scenes, long hours, and moral dilemmas lead to burnout, PTSD, and substance misuse.

Strategies for Mitigation and Adaptation

Addressing the intersection of climate change and mental health demands integrated, multi‑tiered approaches.

A. Emergency Preparedness and Response

-

Mental Health First Aid Training

Equipping community volunteers and emergency teams with psychological first aid skills to provide immediate emotional support. -

Mobile Crisis Units

Deploying interdisciplinary teams that combine medical care with counseling services in disaster zones. -

Telehealth Platforms

Leveraging digital tools to deliver therapy and peer-support groups when physical access is limited.

B. Community Resilience Building

-

Green Infrastructure Projects

Developing parks, urban forests, and green schoolyards to reduce heat islands and promote psychological restoration. -

Community Gatherings and Support Networks

Facilitating regular meetings for survivors to share experiences, strengthening social bonds. -

Cultural Preservation Initiatives

Documenting traditional ecological knowledge and rituals to maintain community identity amid environmental change.

C. Policy and Advocacy

-

Cross‑Sector Collaboration

Integrating mental health considerations into climate policy at municipal, national, and international levels. -

Funding Mechanisms

Allocating dedicated grants for climate‑related mental health research and services. -

Insurance and Social Safety Nets

Expanding coverage for disaster-related mental health treatments, ensuring affordability.

D. Clinical Interventions

-

Trauma‑Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

Adapting evidence-based modalities to address disaster-related PTSD and anxiety. -

Mindfulness and Stress‑Reduction Programs

Incorporating practices such as meditation, yoga, and art therapy to manage eco‑anxiety and solastalgia. -

Group Therapy Models

Facilitating peer support that fosters shared coping strategies and communal healing.

E. Public Education and Awareness

-

Awareness Campaigns

Utilizing social media, schools, and community organizations to disseminate information on climate‑health links. -

School Curricula Enhancements

Introducing modules on environmental science intertwined with psychosocial coping skills. -

Media Engagement

Encouraging responsible journalism that highlights resilience stories alongside warnings, avoiding sensationalism.

Case Studies: Lessons from the Field

A. Australian Bushfires (2019–2020)

-

Communities affected by unprecedented wildfires reported elevated rates of anxiety and depression one year post‑event.

-

Local health services instituted “bushfire clinics,” offering free counseling and community art programs to process trauma.

B. Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico (2017)

-

Following widespread infrastructure collapse, a telepsychiatry pilot connected remote island communities with mainland U.S. clinicians.

-

Preliminary evaluations noted reduced wait times and high patient satisfaction.

C. Drought‑Stricken Regions in Sub‑Saharan Africa

-

Agricultural communities facing crop failures saw rising suicide rates among farmers.

-

International NGOs collaborated with local leaders to establish peer‑support cooperatives and microfinance for diversification of income.

Research Gaps and Future Directions

While the link between climate change and mental health is evident, significant gaps remain in research and practice.

A. Longitudinal Studies

-

Few studies track mental health outcomes over multiple years post-disaster, limiting understanding of chronic impacts.

B. Cultural Contextualization

-

More research is needed on how cultural factors influence resilience and help‑seeking behaviors across diverse populations.

C. Cost‑Benefit Analyses

-

Evaluating economic returns of mental health interventions within climate adaptation budgets can inform policymaking.

D. Integration with Physical Health

-

Holistic models that address comorbidities—such as cardiovascular disease exacerbated by heat stress and anxiety—are underdeveloped.

E. Climate Migration Mental Health

-

Investigating the psychosocial effects of planned relocations and urban settlement patterns for climate refugees.

Call to Action

Climate change is not merely an environmental or economic crisis; it is a human crisis that extends to the core of our psychological well‑being. As temperatures rise and disasters escalate, the global community must:

-

Prioritize Mental Health in climate resilience planning at every governance level.

-

Invest in Research that illuminates pathways from environmental stressors to mental health outcomes.

-

Empower Communities through education, local capacity building, and culturally appropriate interventions.

-

Foster Cross‑Disciplinary Collaboration among climate scientists, mental health professionals, urban planners, and policymakers.

By acknowledging and addressing the mental health dimensions of climate change, we can build more resilient societies that withstand environmental shocks—not just physically, but emotionally and psychologically as well.