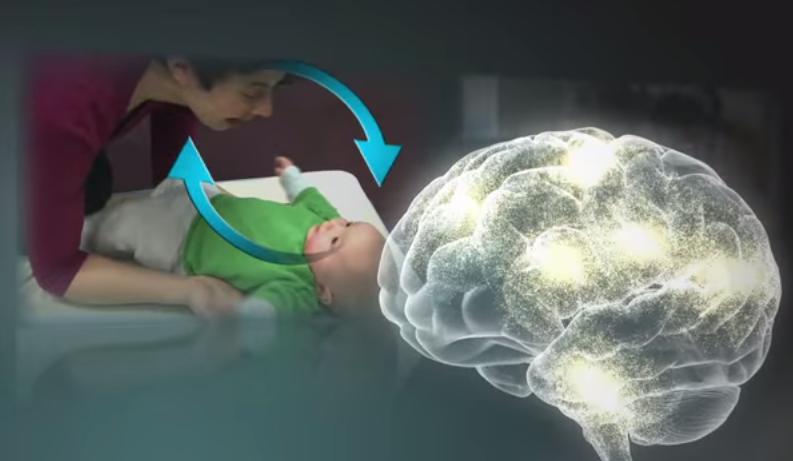

Experiencing hardship during childhood can leave lasting imprints on the developing brain. Early adversity—such as neglect, abuse, household dysfunction, or chronic stress—triggers a cascade of biological, psychological, and social processes that reshape neural architecture. This article explores how childhood adversity affects brain development, the underlying mechanisms, the cognitive and emotional consequences, and strategies to foster resilience and healthy growth.

1. Defining Childhood Adversity

Childhood adversity encompasses a broad range of negative experiences that occur before age 18. These include:

A. Physical abuse

B. Emotional abuse

C. Sexual abuse

D. Neglect (physical or emotional)

E. Household dysfunction (e.g., parental mental illness, substance abuse, incarceration)

F. Community violence

G. Poverty and food insecurity

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) measures these domains, revealing that higher ACE scores correlate strongly with poorer health, emotional, and cognitive outcomes in adulthood.

2. Sensitive Periods in Brain Development

The brain undergoes rapid and region‐specific growth during childhood. Two key sensitive periods include:

A. Early childhood (0–5 years): Synaptogenesis peaks; experiences lay foundational circuits.

B. Adolescence (10–19 years): Synaptic pruning refines networks; prefrontal cortex matures, shaping executive functions.

Adversity occurring during these windows can disproportionately disrupt critical processes like synapse formation, myelination, and cortical thinning.

3. Biological Mechanisms

3.1 Stress‑Response System Dysregulation

Chronic stress activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevations in cortisol and other glucocorticoids. Prolonged HPA hyperactivity can:

A. Reduce dendritic complexity in the hippocampus, impairing memory.

B. Alter amygdala growth, heightening threat reactivity and emotional intensity.

C. Delay prefrontal cortex maturation, undermining impulse control and planning.

3.2 Neuroinflammation

Early adversity can prime microglia—the brain’s immune cells—to a pro-inflammatory state. Heightened neuroinflammation:

A. Disrupts synaptic pruning, leading to either overabundance or deficit of connections.

B. Compromises oligodendrocytes, weakening myelination and neural transmission speed.

3.3 Epigenetic Modifications

Stressful experiences modify gene expression via DNA methylation and histone changes. For example:

A. Glucocorticoid receptor genes: Altered methylation reduces receptor density, perpetuating HPA dysregulation.

B. BDNF (Brain‑Derived Neurotrophic Factor) genes: Methylation changes lower BDNF availability, limiting synaptic plasticity.

4. Structural and Functional Brain Changes

4.1 Hippocampus

– Volume reduction correlates with impaired declarative memory and learning difficulties.

– Connectivity changes disrupt the balance between hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, affecting context processing.

4.2 Amygdala

– Enlargement intensifies emotional reactivity, particularly to threat cues.

– Hyperconnectivity with sensory regions leads to heightened vigilance and anxiety.

4.3 Prefrontal Cortex

– Cortical thinning in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex weakens working memory and cognitive flexibility.

– Delayed maturation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex impairs emotion regulation and decision‑making.

4.4 White Matter Integrity

– Reduced fractional anisotropy in corpus callosum and association tracts slows inter‐regional communication.

– Altered myelination compromises executive functions, attention, and processing speed.

5. Cognitive and Behavioral Consequences

5.1 Learning and Academic Achievement

Children exposed to adversity often exhibit:

A. Attention deficits: Difficulty sustaining focus in class.

B. Executive dysfunction: Struggles with planning, organization, and impulse control.

C. Language delays: Reduced vocabulary and verbal skills.

5.2 Emotional and Social Outcomes

A. Increased anxiety and depression: Chronic HPA activation predisposes to mood disorders.

B. Impaired social cognition: Difficulty interpreting social cues and forming trust.

C. Aggressive behavior: Heightened threat perception fuels reactive aggression.

5.3 Risky and Health‑Endangering Behaviors

A. Substance use: Self‑medication to dampen stress or emotional pain.

B. Disordered eating: Coping with anxiety or lack of control.

C. Self‑harm and suicidality: Attempting to manage overwhelming distress.

6. Protective Factors and Resilience

While adversity poses significant risks, certain factors buffer against negative outcomes:

A. Secure attachment: A stable caregiving relationship fosters emotional safety and self‑regulation.

B. Consistent support systems: Extended family, mentors, or community programs provide resources and modeling.

C. Adaptive coping skills: Teaching mindfulness, problem‑solving, and emotional literacy strengthens resilience.

D. Access to mental health services: Early intervention reduces long‑term impairment.

7. Interventions to Mitigate Impact

7.1 Early Childhood Programs

– Home Visiting Services: Trained nurses support parenting skills and monitor child development.

– High‑quality Early Education: Enriched environments promote cognitive and social growth.

7.2 School‐Based Supports

A. Trauma‐Informed Classrooms: Educators trained to recognize and respond to trauma-related behaviors.

B. Social‑Emotional Learning (SEL): Curricula that teach self-awareness, self-management, and social skills.

C. Mentorship Initiatives: Pairing students with caring adults to foster trust and guidance.

7.3 Clinical Treatments

– Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Addresses maladaptive thoughts and builds coping strategies.

– Play Therapy and Art Therapy: Allows expression of trauma through creative, non‑verbal channels.

– Family Therapy: Strengthens communication and support within the family system.

8. Policy and Community Implications

8.1 Poverty Reduction

Economic support through:

A. Cash assistance programs

B. Affordable housing initiatives

C. Universal preschool

These policies alleviate stressors that underlie adversity.

8.2 Child Protection and Family Support

A. Strengthening child welfare systems: Early identification of at-risk families and swift, supportive interventions.

B. Parental leave policies: Allow caregivers time to bond and reduce stress.

C. Accessible mental health services: Insurance coverage and community clinics ensure care for low‑income families.

8.3 Public Awareness and Education

– Media campaigns to destigmatize mental health care.

– Training for healthcare providers to screen for ACEs and refer to resources.

Conclusion

Childhood adversity exerts profound and multifaceted effects on brain development, manifesting in altered structure, connectivity, and function. These neural changes underlie the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral challenges faced by affected individuals. However, a wealth of protective factors and targeted interventions—ranging from nurturing relationships to policy reforms—offer hope. By understanding the biology of adversity and championing resilience‑building strategies, caregivers, clinicians, educators, and policymakers can collaborate to ensure that every child has the opportunity to thrive.