Climate change has increasingly become not only an environmental challenge but also a profound public health crisis. Recent studies reveal a troubling link between the intensification of extreme weather events—such as heatwaves, floods, wildfires, and hurricanes—and a surge in mental health disorders across vulnerable communities. From heightened anxiety and depression to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the psychological toll of climate change is mounting worldwide. This article explores the multifaceted pathways through which climate change aggravates mental well-being, evaluates the social and economic factors at play, and proposes targeted strategies for prevention, adaptation, and resilience.

I. Direct Impacts of Extreme Weather on Mental Health

A. Heatwaves and Psychological Distress

- Physiological pathways: exposure to extreme heat disrupts sleep patterns, elevates irritability, and exacerbates mood disorders.

- Epidemiological evidence: regions experiencing more frequent heatwaves report a direct rise in emergency psychiatric visits and hospitalizations.

B. Flooding, Displacement, and Trauma

- Loss of home and community: forced evacuation undermines social support networks and sense of safety.

- Acute stress reactions: survivors commonly manifest symptoms resembling acute stress disorder, which may evolve into chronic depression or PTSD.

C. Wildfires and Chronic Anxiety

- Smoke exposure and neuroinflammation: particulate matter can trigger neurological pathways linked to anxiety and cognitive decline.

- Prolonged evacuation and relocation stress: uncertainty over property damage and insurance claims fosters persistent worry and helplessness.

D. Hurricanes and Collective Grief

- Community trauma: widespread disaster leads to collective mourning for lost lives, livelihoods, and landmarks.

- Post-disaster mental health services: gaps in resources often leave rural and low-income populations without timely care.

II. Indirect Pathways: Economic, Social, and Cultural Stressors

A. Economic Insecurity and Mental Strain

- Crop failures and livelihood loss: farmers face acute financial hardship, driving rates of suicide and substance abuse.

- Insurance premiums and housing costs: rising expenses increase stress among middle- and low-income families, contributing to depressive episodes.

B. Social Inequities Exacerbated

- Disproportionate burden on marginalized groups: communities of color and Indigenous populations often lack resources and infrastructure to adapt.

- Environmental justice and mental health: unequal exposure to pollution and climate hazards correlates with higher rates of anxiety and mood disorders.

C. Cultural Displacement and Identity Loss

- Indigenous knowledge and place attachment: relocation severs cultural bonds to ancestral lands, fostering grief and identity crises.

- Language loss and intergenerational trauma: displacement interrupts the transmission of heritage, compounding psychological distress.

III. Vulnerable Populations and Differential Impacts

A. Children and Adolescents

- Developmental sensitivity: early-life exposure to disasters can disrupt emotional regulation and cognitive development.

- School closures and education interruptions: academic stress and social isolation fuel anxiety and depression.

B. Elderly and Chronically Ill

- Physiological vulnerability: heat stress and poor air quality aggravate pre-existing health conditions and cognitive decline.

- Social isolation: limited mobility and reduced social networks lead to loneliness and increased suicide risk.

C. Frontline Responders and Aid Workers

- Compassion fatigue: repeated exposure to suffering and disaster sites intensifies burnout and secondary PTSD.

- Insufficient mental health support: lack of debriefing protocols exacerbates insomnia, irritability, and substance misuse.

IV. Research Insights and Knowledge Gaps

A. Need for Longitudinal Studies

- Tracking mental health trajectories over decades to quantify cumulative climate stress.

- Integrating biomarkers of stress to correlate physiological changes with psychological outcomes.

B. Geographic and Cultural Diversity

- Understudied regions: low- and middle-income countries bear the brunt of climate impacts yet lack robust data.

- Culturally adapted assessments: standard diagnostic tools may miss culturally specific manifestations of distress.

C. Intersectional Approaches

- Examining the interplay of gender, race, socioeconomic status, and climate vulnerability.

- Tailoring interventions to address overlapping sources of disadvantage and trauma.

V. Strategies for Prevention and Resilience

A. Strengthening Public Health Infrastructure

- Early warning heat alert systems coupled with community mental health outreach teams.

- Mobile clinics and telemedicine for rapid deployment after floods, fires, and storms.

B. Community-Based Adaptation and Social Cohesion

- Peer-support networks: training local volunteers to provide psychological first aid.

- Community resilience hubs: multi-use centers offering disaster preparedness training, social gatherings, and mental health workshops.

C. Policy Interventions and Funding Mechanisms

- Climate-sensitive insurance reform: subsidies for flood and fire insurance tied to mental health service access.

- Dedicated mental health funds within national climate adaptation budgets.

D. Climate Education and Advocacy

- Integrating climate literacy into school curricula to build adaptive coping skills and agency among youth.

- Public awareness campaigns: destigmatizing mental health care and promoting collective action to reduce emissions.

VI. Clinical Approaches and Therapeutic Innovations

A. Trauma-Informed Care Models

- Incorporating environmental grief into therapeutic frameworks: acknowledging loss of ecosystems within grief counseling.

- Training clinicians on climate-specific stressors: workshops on heat-related sleep disorders, eco-anxiety, and disaster trauma.

B. Digital Interventions and E-Mental Health

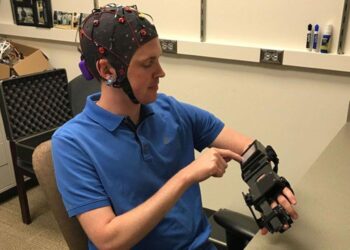

- Smartphone-based cognitive behavioral therapy apps: leveraging AI to deliver just-in-time coping strategies during heatwaves or evacuations.

- Virtual reality exposure therapy: simulating past disaster scenarios to treat PTSD in controlled settings.

C. Mind-Body Practices and Nature-Based Therapies

- Ecotherapy: structured outdoor activities that reconnect individuals with healing environments.

- Yoga, mindfulness, and breathing exercises tailored to manage eco-anxiety and stress.

Conclusion

Climate change is no longer a remote future threat: its impacts on mental health are immediate, profound, and far-reaching. By recognizing the myriad pathways—direct, indirect, and intersectional—through which environmental change exacerbates psychological distress, stakeholders can design more effective prevention, adaptation, and treatment strategies. Robust research, community engagement, and climate-sensitive policy reforms are essential to safeguard mental well-being in an era of global warming. Tackling the mental health crisis fueled by climate change demands integrated action across health systems, governments, and civil society to build resilience, foster hope, and ensure equitable access to care.