Extreme weather events are no longer isolated anomalies—they are becoming the defining characteristic of our planet’s changing climate. Recent analyses estimate that by mid‑century, over 70% of humanity will experience some form of extreme weather annually, from crippling heatwaves to catastrophic floods. This seismic shift poses profound challenges to health, infrastructure, food security, and economic stability worldwide. In this comprehensive article, we explore the drivers behind this phenomenon, the regions most at risk, the cascading impacts on societies, and the strategies needed to bolster resilience.

A Planet on the Brink

Global average temperatures have risen by more than 1.2 °C since pre‑industrial times, fueling more frequent and severe meteorological extremes. From deadly wildfires in Australia and California to historic monsoons in South Asia, the evidence is clear: climate change is intensifying the hydrological cycle, pushing ecosystems and human communities to the edge. With over five billion people projected to face unprecedented weather hazards each year, understanding these threats is critical for policymakers, businesses, and citizens alike.

Drivers of Extreme Weather

Several interlinked processes amplify extreme events:

A. Greenhouse Gas Accumulation

-

Burning fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O), trapping heat in the atmosphere and raising global temperatures.

-

Higher temperatures increase evaporation rates, supercharging storms and shifting rainfall patterns.

B. Atmospheric Circulation Shifts

-

Warming polar regions weaken the jet stream, causing weather systems to stall longer over a region and intensify heatwaves or rainfall.

C. Ocean Heat Content Rise

-

Oceans absorb over 90% of excess heat. Warmer seas intensify tropical cyclones and contribute to sea level rise through thermal expansion.

D. Land‑Use Changes

-

Deforestation reduces evaporation from trees, altering local precipitation. Urban expansion creates heat islands that exacerbate heatwaves.

Regional Hotspots of Vulnerability

While extreme weather will affect all continents, certain areas face disproportionate risks:

A. South and Southeast Asia

-

Home to over two billion people, this region relies on monsoon rains for agriculture. Unpredictable monsoon onset or breaks fuel floods and droughts alike.

-

Low‑lying deltas, such as the Ganges‑Brahmaputra, are prone to storm surge during cyclones.

B. Sub‑Saharan Africa

-

Many nations lack irrigation infrastructure; shifting rainfall patterns threaten staple crops like maize and sorghum.

-

Recurrent droughts exacerbate food insecurity and cross‑border migration.

C. Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

-

Rising sea levels and intensifying hurricanes place entire nations at risk of inundation. Freshwater lenses become saline, and coastal erosion accelerates.

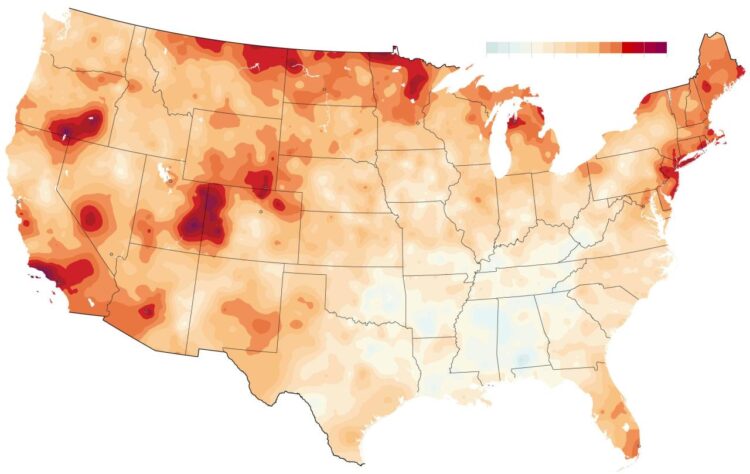

D. Western North America and Mediterranean Europe

-

Prolonged heatwaves and aridification fuel megafires, from California’s forests to Portugal’s shrublands.

-

Water scarcity intensifies competition between agricultural, urban, and ecological demands.

Impacts on Human Health

Extreme weather directly and indirectly undermines public health:

A. Heat‑Related Illnesses

-

Heat exhaustion and heatstroke hospitalize thousands during severe heatwaves. Urban populations face higher risks due to concrete‑dense environments.

B. Vector‑Borne Disease Expansion

-

Warmer, wetter conditions allow mosquitoes carrying malaria, dengue, and Zika to expand into previously cooler zones.

C. Mental Health Stressors

-

Displacement after floods, fires, or storms leads to anxiety, depression, and post‑traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

D. Malnutrition and Waterborne Illnesses

-

Crop failures drive food shortages, while flooding contaminates drinking water sources, causing diarrheal diseases.

Strain on Infrastructure and Economy

Extreme weather disrupts markets, damages assets, and drains public coffers:

A. Critical Infrastructure Failures

-

Heatwaves buckle roads, strain power grids through peak air‑conditioning demand, and warp rail tracks.

-

Coastal storms damage ports, bridges, and shipping routes, slowing global trade.

B. Insurance Market Instability

-

Increasing claims push up premiums or drive insurers out of high‑risk markets, leaving communities unprotected.

C. Agricultural Yield Volatility

-

Droughts reduce harvests; floods drown fields. Commodity price spikes follow, threatening food affordability.

D. Supply Chain Disruption

-

Factory shutdowns and transport delays ripple across global supply chains, affecting manufacturing, retail, and services.

Cascading and Compound Events

One extreme event often triggers another, creating complex disasters:

A. Flood‑Induced Landslides

-

Saturated hillsides collapse, endangering mountain communities and obstructing evacuation routes.

B. Heat‑Driven Wildfires Leading to Air Pollution

-

Fires release particulate matter that degrades air quality hundreds of kilometers downwind.

C. Sea Level Rise Amplifying Storm Surge

-

Even modest sea level increases turn moderate storms into catastrophic floods in coastal cities.

D. Simultaneous Heat and Drought

-

Compound heat‑drought events decimate crops and heighten wildfire risk, overwhelming emergency services.

Socioeconomic Inequities Exposed

The burdens of extreme weather fall unevenly:

A. Low‑Income Communities

-

Often reside in hazard‑prone areas—floodplains, steep slopes, urban heat islands—due to cheaper land.

B. Marginalized Populations

-

Lack resources to prepare, evacuate, or rebuild. Informal settlements may not have resilient housing.

C. Gender Disparities

-

Women, particularly in rural areas, face higher mortality in disasters and greater difficulty accessing relief.

D. Developing Nations

-

Limited fiscal capacity to invest in hard engineering solutions like seawalls or large‑scale irrigation.

Strategies for Adaptation and Resilience

Mitigating risks requires integrated, multi‑tiered action:

A. Nature‑Based Solutions

-

Restoring wetlands and mangroves buffers storm surge and filters pollutants.

-

Urban green spaces reduce heat through evapotranspiration and provide recreational areas that enhance well‑being.

B. Early Warning and Forecast Systems

-

Investing in remote sensing and community‑level messaging saves lives.

-

Mobile alerts guide farmers on optimal planting dates, reducing crop failure.

C. Climate‑Resilient Infrastructure

-

Designing roads to tolerate temperature extremes; elevating homes in flood‑prone areas.

-

Upgrading drainage to cope with intense downpours, avoiding urban flash floods.

D. Socioeconomic Safety Nets

-

Cash‑transfer programs provide liquidity after disasters, preventing descents into poverty.

-

Subsidized insurance schemes promote risk‑sharing and incentivize resilience measures.

E. Policy and Governance Reform

-

Integrating climate risk into national development plans.

-

Enforcing land‑use zoning that restricts construction in high‑hazard zones.

The Role of Mitigation

While adaptation buys time, reducing greenhouse gas emissions remains paramount:

A. Transition to Renewable Energy

-

Phasing out coal and scaling wind, solar, and hydroelectric power cuts CO₂ emissions.

-

Electrifying transport and industry further dislodges fossil fuels from economic growth.

B. Carbon Sequestration

-

Afforestation, reforestation, and improved agricultural practices lock carbon in soils and biomass.

C. Behavioral and Consumption Shifts

-

Promoting plant‑rich diets and reducing food waste lowers methane and CO₂ footprints.

-

Encouraging public transport and low‑emission lifestyles decreases overall energy demand.

Looking Ahead: Preparing for a New Normal

As temperatures climb toward 2 °C above pre‑industrial levels, projections suggest:

A. Daily Exposure

-

Hundreds of millions will live in regions where wet‑bulb temperatures—combining heat and humidity—reach human survivability limits.

B. Mass Displacement

-

Up to 200 million climate migrants by 2050 may uproot communities, challenging global refugee frameworks.

C. Economic Drag

-

The IMF estimates climate‑related losses could shave 10% annually off GDP in the hardest-hit emerging markets.

D. Biodiversity Loss

-

Ecosystems under multiple stressors face collapse, undermining services like pollination, water purification, and soil fertility.

Despite these daunting forecasts, the path forward is not predetermined. Bold policy choices, technological innovation, and community engagement can alter trajectories. By embracing both mitigation and adaptation in equal measure—and by prioritizing equity in every intervention—societies can weather the storm ahead.

Conclusion

Extreme weather events are poised to impact over 70% of the global population, reshaping everything from the safety of our homes to the stability of world markets. Addressing this crisis demands an “all‑hands, all‑sectors” approach: governments must enact forward‑looking policies; businesses need to integrate climate risk into core strategies; civil society and individuals should demand accountability and adopt sustainable lifestyles. Only through collective resolve can we forge a resilient future, safeguarding both people and the planet against the accelerating onslaught of extreme weather.